Note: This is the second installment in what we hope is a semi-regular series on people who make ADV gear by hand. We’re open to suggestions of other businesses or individuals who work this way, because it’s a rare thing these days—Ed.

If you’re a serious street-riding motorcyclist in North America, sooner or later, you’ll come across Aerostich—a company whose customers aren’t exactly cult-like, but they certainly are lifelong devotees. Aerostich has a mail-order/e-warehouse retail business that stocks products savvy riders will find useful, especially if they’re commuters or long-distance travellers. But, the company’s main business is its line of made-in-Minnesota riding gear, including one-piece and two-piece suits, off-road jerseys, windproof sweaters, heated gear, rainsuits and other practical attire. Unlike a lot of motorcycle gear today, the emphasis is on function over fashion, but people keep buying it.

Why do people become lifelong customers of a brand with this image, in an age where sporty performance or menacing scowls sell moto gear? And how does a company in Duluth, Minnesota continue to make things here in the US at a time when production for almost all its competition has been sourced overseas? Simple: It’s because from Day One, Aerostich gear has been specifically designed to meet the needs of serious motorcyclists. And from Day One, Aerostich was built to rise from the ashes of disappearing American industry.

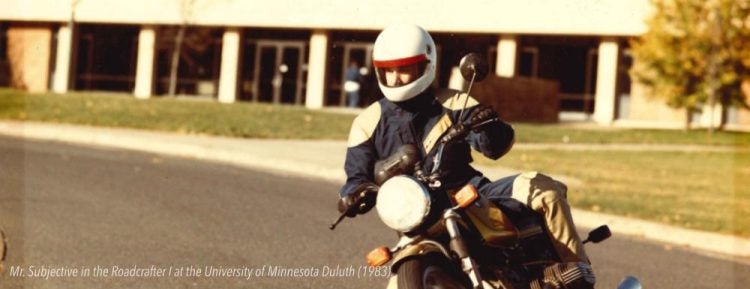

A young Andy Goldfine test-runs his new one-piece suit. Photo: Aerostich

Andy Goldfine’s Great Adventure

Aerostich was founded and is still run by Andy Goldfine, who founded the company in the early 1980s. Goldfine was a philosophy student who came from a family of entrepreneurs, but he wasn’t a roadracer or anything like that—he was just a guy who liked riding his motorcycle everywhere. So why start a gear-making company?

Simple. Goldfine founded Aerostich to suit himself, both literally and figuratively.

Now older and wiser, Goldfine is a unique individual in the motorcycle industry. Part entrepreneur, part moto-philosopher, he’s the kind of guy who’s explored and maybe even figured out the questions posted by Robert Pirsig in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Photo: Motorcycle.com

When Goldfine was a young man, he realized that he didn’t really care to move far away from his Minnesota home. He liked where he lived, and in his words, he wasn’t autistic, but he was pretty close to it—and he wanted some sort of career that was a good match for his skills and personality and let him remain in Duluth. He cast his eyes around, and the answer was waiting for him in his day job.

Forty years ago, we were in the early stages of North America’s de-industrialization, and Goldfine was working for an company that wanted to auction the equipment from a recently closed garment factory. He noticed that industrial sewing machines at the time worth $1,500-$2,500 were selling at such auctions for $250-$300—”They were worth nothing, because people were going bankrupt.” He got some of those sewing machines for himself, moved them into an empty candy factory building, and started figuring out what he was going to make with them.

On a KTM 1290 Super Adventure S, in the California sun. Zac’s R3 looks a lot more grungy than it did when this photo was taken, but it’s still waterproof and a go-to choice when he’s touring, especially in cold weather. Photo: James Lissimore/KTM

That building is the same place that Aerostich is located today, near Duluth’s waterfront, but it looks a lot different now—it’s full of manufacturing equipment, people, and riding gear.

Goldfine wasn’t an industrialist, but when he started setting up his operation, he knew the machines he had were made for sewing heavy-duty garments… and he knew the outdoors clothing industry was already filled with stiff competition. He needed a niche, and figured the most market leverage he could get was by starting something entirely new, creating a kind of motorcycle riding gear that did not exist. That’s where the Aerostich Roadcrafter was born. Goldfine sketched what he wanted, hired a patternmaker and sample sewers, and started making suits.

Spreading the word

Some riders immediately saw the advantages of the new gear; others were slow to see the game-changing possibility of lightweight, waterproof synthetic crash-proof fabric combined with visco-elastic armor.

The Aerostich catalog was a smart marketing method that benefited riders by exposing them to new gear choices. Image: Aerostich

How would Goldfine spread the gospel of better gear? Back in the mid-’80s, print mags steered consumer interest, and almost all those print mags were based in southern California. Goldfine packed up his bike and headed west, sleeping on his cousin’s couch for a week as he visited the magazines in person to show off his suits’ advantages. Motojournos have been wearing them ever since.

I visited Aerostich’s headquarters in 2013; at that time, they had a display of motorcycle magazine covers featuring journos sporting an Aerostich suit. There were a lot of magazines displayed, and operations leader Lynn Wisneski told me they’d stopped putting them on the wall when they ran out of space. Now, more than a decade later, I can’t imagine how many more photos would be on that wall if you added in all the online motojournos who have relied on Aerostich.

But getting magazine writers into Aerostich suits (and getting Aerostich ads into magazines) was only one part of Goldfine’s strategy. Next, he started publishing a mail-order catalog, inspired by the publications that adventure outfitters like Abercrombie & Fitch had published a half-century earlier. Back then, if you wanted to go on a hunting trip to the Catskills, or Alaska, or the Congo, Abercrombie & Fitch had a catalog with everything you needed.

The Aerostich catalog (see the current version here) was the same, but for motorcyclists, and in the days before the Internet retail takeover, it served a very useful function.

Now, cheap Asian manufacturing means motorcycle stories can carry a lot of product without worrying so much about overhead, and of course, an Internet business can stock whatever it wants and sell all over the world. But before those factored strongly in the world of motorcycling, you couldn’t expect to just walk into a moto dealership and find whatever you needed (or didn’t even know you needed). The Aerostich catalog helped educate riding consumers by showing them useful products, and explaining them… and selling them.

The Cousin Jeremy is an example of Aerostich’s willingness to play outside the lines. Basically, they turned their textile Roadcrafter into a retro waxed-cotton suit. While it doesn’t have the same performance as the synthetic fabrics, it’s probably a lot more sustainable in the long term, as riders can re-wateproof the suit themselves. Photo: Laura Deschenes

Aerostich did change quickly with the times, though; the company had Duluth’s first e-commerce site all the way back in 1994, and even though the current catalog is smaller than its forbears, Aerostich’s website has a wide range of products selected for the same reasons as always: They’re useful to the moto-consumer.

Aerostich today

While a lot of riders love Aerostich, there are others who complain the company needs to update its designs with more mesh or other tweaks.

Goldfine doesn’t think so; he’s happy to continue to make gear to a refined and tested pattern that works. He says there’s a difference between rapidly-changing technologies like consumer electronics compared to something like a riding suit, which does the same job in 2024 that it did in 2004, or 1984: It protects the rider from injury and from the elements.

He still has customers coming back for more, some of them on their third or fourth Aerostich, and he wants to continue to offer them what they want. And, Aerostich is still a small company, without the deep pockets to try ideas that might not pan out—and without the inflated product margins that some other companies see. Their products are still made in the Duluth factory (see webcam feed here!), and that means paying North American wages.

Who works for Aerostich these days? Goldfine recites an interesting job description: “Someone who is looking for a career vocation, with full benefits, who perceives personal and community value in what we do here. Socially well-adjusted, reliable, smart, good with hand-work, honest… someone who wants to be in all areas of their life both useful and kind.”

These days, a few dozen people are cutting and sewing suits and other gear together, or are involved in the sales and shipping, or otherwise continuing to equip motorcyclists. All kinds of people work there, from college kids who only spend a few short years at the factory while working through school to lifers who spend decades there. Goldfine knows he could make more profit if he moved all production overseas, but he thinks what he’s doing is the ethical way to support motorcycling and his community and besides, what he’s doing suits him, just like it did 40 years ago when he started: ” I like making stuff. I like this kind of work and I am surrounded by people who also like doing this kind of work.” That’s a line of reasoning that’s pretty hard to argue with.